Mentorship and job stability: Addressing 2 pressing challenges for young adults aging out of foster care

“Sometimes I joke that I’m the only person I know who has been orphaned twice.”

Nearing age 50, Daniel Dunning has found a lightheartedness when he speaks about his experience within the adoption and foster care system. It’s a disposition that has come over time and because, against the odds, he landed on his feet as an adult – a rite of passage that many youths leaving foster care never experience.

Growing up in foster care

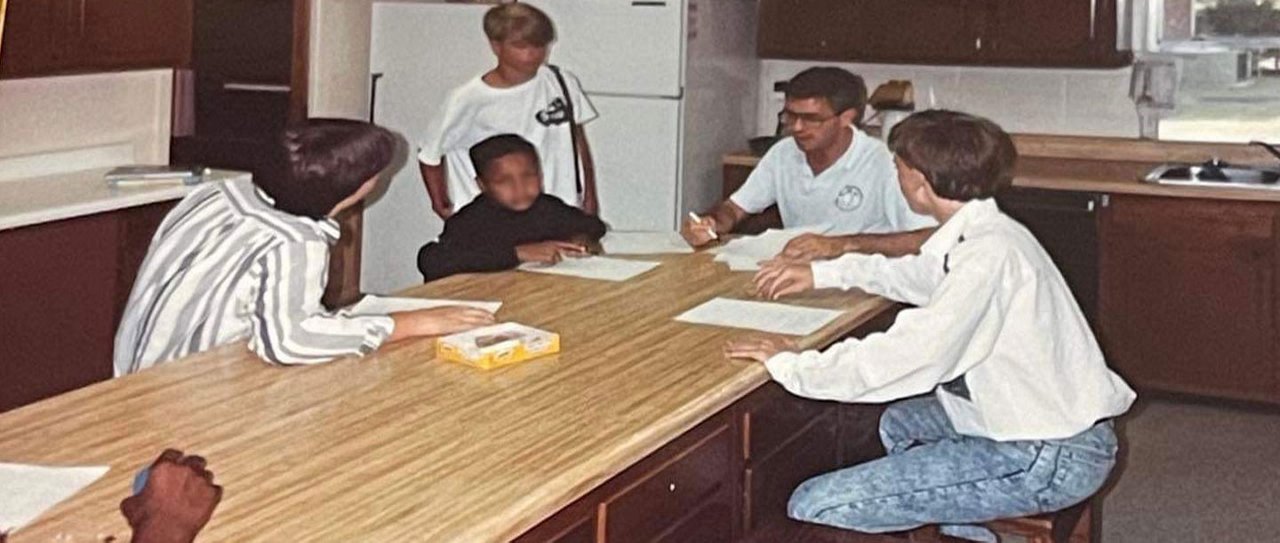

Dunning was first adopted at three months old. As a teenager, he was removed from his adoptive home because of emotional neglect. From there, he entered a “boys’ home” – a giant house where he lived with seven other boys, as well as a tag-team of social workers and caretakers.

“I was one of the lucky ones,” Dunning says. At that time, he was the only one of his cohort to enroll in higher education upon graduating high school. “A couple of the boys went into the military, some ended up in and out of jail, and others just disappeared.”

Dunning cites his adoptive parents as one of the biggest reasons he went to college. “My adoptive father was college educated, and there was always an expectation that their other children and I would go to college.” That mindset held sway even after Dunning transitioned into the foster care system at age fifteen.

When he was at NC State University, Dunning kept his experiences as a child of the foster care system a secret. At that age, he was self-conscious about his upbringing and the stigma it entailed.

Like most children who age out of the foster care system, Dunning had no strong familial ties, leaving him with limited financial and emotional support. While he was able to secure Pell Grants and scholarships to cover his tuition, he remembers selling plasma to cover the additional expenses of being a college student. He worked other odd jobs during this time as well, which tugged his attention and resources away from his studies. “I had to get a job to support myself, and I needed transportation. I was always driving cars with more than 200,000 miles on them, and they were always breaking down. and then I either had to pay for repairs or buy another car. I could never seem to break the cycle.”

All in all, he took seven years to graduate college, flunking out once during the process. But he did finally break the cycle; he found enough footing to graduate with honors, in doing so, he became somewhat of an anomaly. Recent research shows that just 3-4% of youth who age out of foster care obtain a four-year degree. Living expenses, unreliable access to housing and high-speed internet, and lack of academic and financial support are barriers to completing a degree in higher education. Dunning recalls, “I didn’t have family, only my peer group. No one ever asked about my grades.”

Challenges for adults who grew up in foster care

All young adults leaving the foster care system – whether they go to college or not – face similar, significant obstacles: They often find it more difficult to secure resources like stable housing, employment, reliable transportation, financial literacy and social support, to name a few. Data from the Annie E. Casey Foundation about transition age youth nationwide show that:

- 29% report experiencing homelessness between the ages of 19 and 21

- Just 57% report being employed, either full- or part-time, by age 21

- Approximately 20% report being incarcerated between the ages of 17 to 21

Dunning says, “Most of these kids are not thinking long-term [when they age out of foster care]. They’re thinking of how to survive.” From his personal experience, Dunning knows the importance and power of building relationships with these young adults and checking-in to show that someone cares.

Mentoring adults aging out of foster care

While Dunning provides his apprenticeship mentee with professional advice, he also fulfils a much more nuanced, important role: addressing gaps in life experience. “Job stability offers these young adults a future that can lead to a career path. But they also need help with personal circumstances, like I did,” Dunning says. “For example, I have been able to provide guidance to my mentee on the importance of building credit for both housing stability and transportation reliability. And then there’s also familial life – like setting healthy boundaries with biological and adoptive family members. I’ve dealt with similar circumstances. It’s all about finding a balance that’s not disruptive.”

He added, “None of us is born with this knowledge. It comes from life experience.”

Dunning also received informal mentorship during his transition out of foster care. One mentor, Fessor D. McCoy, was the head of the group home where he lived. The two still keep in touch today. Although their relationship has changed, Dunning wants to pass on the benefits he received as a mentee: “I want to help make the transition into adulthood easier for these kids,” he says. “I just listen to what’s going on, and occasionally insert my anecdotes or experience. But mostly I just listen because that’s the most important thing you can do to show you care.”

Daniel Dunning is an employee of Blue Cross NC who works within our IT division.

Browse related articles

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability in its health programs and activities. Learn more about our non-discrimination policy and no-cost services available to you.

Information in other languages: Español 中文 Tiếng Việt 한국어 Français العَرَبِيَّة Hmoob ру́сский Tagalog ગુજરાતી ភាសាខ្មែរ Deutsch हिन्दी ລາວ 日本語

© 2025 Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina. ®, SM Marks of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association, an association of independent Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans. All other marks and names are property of their respective owners. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina is an independent licensee of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association.